By Tai Jia Xuan

Diploma in Creative Writing for Television and New Media

Singapore Polytechnic

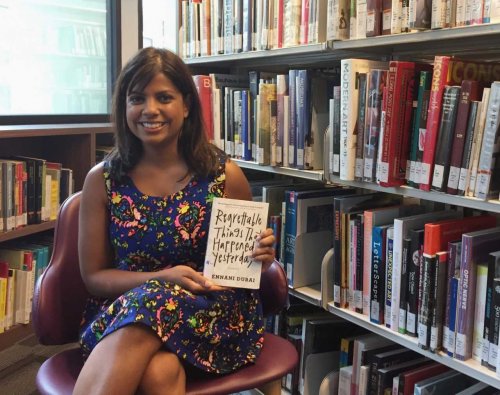

Jennani Durai’s first fiction book, Regrettable Things that Happened Yesterday, was shortlisted for the 2018 Singapore Literature Prize. (Photo by Saraswathy D/O Kumaran)

Growing up in Singapore, it never struck Jennani Durai that there were few stories about Indian Singaporeans like her.

And even after becoming more aware of this issue, she remained sceptical about its relevance to society.

“Indians are 7 percent of Singapore, so I was like, who wants to read about 7 percent of a tiny dot on the map?” Jennani laughs.

But when she debuted her first solo book, Regrettable Things that Happened Yesterday, the 32-year-old writer and former journalist received far greater reception than she anticipated.

Shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize 2018, the book features mostly Indian Singaporean characters in a collection of ten short stories linked by the motif of newspapers.

Writing fiction, her passion

Having always been interested in writing fiction, Jennani began working on a few short stories while still a journalist for the Straits Times. After moving to Guatemala with her husband, she focused on finishing Regrettable Things that Happened Yesterday, publishing it with Epigram in 2017.

Her six years as a journalist honed her fiction writing skills as meeting different people and hearing their stories helped her “develop the basic tool for writers: empathy.”

Although the book’s recurring motif of newspapers started out as a coincidence, Jennani believes in the power of newspapers and is glad that they play such a huge part in her book.

Minority representation in English fiction

Besides newspapers, Jennani believes in having more Indian Singaporean stories in English fiction so that minority readers can read about themselves and feel represented here.

She recalls when she first read Sugarbread by local author Balli Kaur Jaswal and was stunned by the number of things she connected with in the book.

One part that stood out was when the main character, an 11-year-old Indian Singaporean girl, encountered a racist bus driver. Jennani had the same experience in real life and it made her wonder, “does that happen to all little Indian Singaporean girls in Singapore?”

Similar to her profound moment of connection, people have told Jennani that they empathised with her stories, having gone through them as well.

Through weaving personal experiences into her book, Jennani hopes to show that Indian Singaporean experiences are no different from other Singaporeans as “we are also just Singaporeans living our lives.”

While stressing the importance of having minorities as protagonists, Jennani also understands the challenges of writing local fiction that aspiring writers may face.

“Growing up, you are reading all about white kids,” she says. “Even people who want to be writers… become writers because of the books they have read. So, it is almost hard to start writing about people like you when you want to write about things you’ve already read.”

Her advice to young writers is to write what they want to read or see more of in Singapore literature.

“You probably already have inspiration from the things you’ve seen around you in Singapore,” Jennani says, “or what you’ve imagined Singapore to be.”

By Marianne Charmaine Ng Pui Shuet

Diploma in Creative Writing for TV and New Media

Singapore Polytechnic

Author Euginia Tan remembers that her first foray into writing as a teen bored her to tears. She was helping her mother translate an interview of a local actress, and words to her back then were just a functional means of communication. It was only when she started publishing her work did she come to realise the power words actually held.

Euginia’s first poetry collections, Songs about Girls and Playing Pretty, tackle the topic of mental health in Singapore. And the 27-year-old speaks from experience, having struggled with depression during her teen years.

“There were not many resources to tell young people that, “Hey you know, you can do whatever you want even though you have this ailment,” she says. “It was always about hiding your disorder; it was always about telling people you had to overcome it. I wanted people to say, “Hey, yeah I have this, but I’m still going to do what I love anyway.”

Her third collection, Phedra, draws inspiration from Greek mythology and finds parallels in the present day. It also helped her deal with the loss of both her grandmothers, who passed away within months of each other as she was writing it.

A Nod to Self-Published Authors

Phedra was shortlisted for the 2018 Singapore Literature Prize (SLP). For many, the nomination would be a symbol of accomplishment. For Euginia, it also represents acceptance. She took the unusual route of self-publishing Songs about Girls and Playing Pretty and says there is still “a lot of judgement” about starting out that way. Euginia hopes that the literary community will become more welcoming of self-published authors and believes the SLP shortlist is a step in the right direction.

Apart from being a poet, Euginia is a playwright. Her Tuition received local praise for highlighting the strong bonds that teachers can form with their students. She is currently in a two year mentorship with The Finger Players, under Programme Director Chong Tze Chien.

“(The mentorship) really made me change the direction in which I’m taking my writing, and that made me so much more conscious of wanting to bring my craft out there to different types of audiences,” she reveals.

And while Euginia holds writing dear, she believes that integral to the process of doing it well is for authors to know their roots, and that is “that very simple place of being a reader.”

By Althea Duncombe

Diploma in Creative Writing for Television and New Media

Singapore Polytechnic

Desmond Kon Zhicheng- Mingdé is an avid lover of words and poetry.

(Photo Credit: Althea Duncombe)

Fourteen years ago, Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé wrote down three wishes on a napkin with some friends. One wish was to author a poetry collection and another was to win a literary prize. He has fulfilled both of those wishes many times over – including having won the prestigious Singapore Literature Prize.

His third wish, however, remains a secret.

“Not because it’s anything scandalous or anything,” he joked, “but pretty much all my books are trying to live up to that last wish on the napkin.”

Desmond, 47, is an author, poet and artist. He is known for his fondness for postmodernism and Dadaism – a literary and artistic movement that originated in Switzerland in the early 1900s as a response to the rise of capitalism, war and the modern age.

The life of a writer

When Desmond was little, he enjoyed poems, but it was the time he spent studying in the United States that truly sparked his interest in poetry.

He went on to publish various poetry collections and other books and soon became the first Singaporean to win the Gold award in the Poetry category at the Benjamin Franklin Book Awards.

He has even conjured up poetry terms and styles of his own, such as the ‘asingbol’ – a variation of Twitter poems that comprise exactly 140 characters inclusive of spaces and punctuation.

Anti-art style

Desmond loves all art movements, but Dadaism appears to hold a special place in his heart.

‘Dada’ is a nonsense word, while ‘Dadaism’ takes that nonsense and transforms it into a work of art.

Desmond says that Dadaism, which is sometimes known as ‘anti-art’, “opened a lot of doors and made art more accessible to the public”. With it, even an upturned urinal can be considered art.

“They really overturned that sort of elitist idea of what art is and now art has become much more exciting,” he explains enthusiastically. “Ready-made objects can be turned into art.”

As for postmodernism, Desmond describes it as always questioning the metanarrative, as well as wondering what sort of information, knowledge or history out there is constructed.

“It doesn’t take for granted a lot of truths that we take for granted,” Desmond muses. “It frees up the human spirit, the mind and it constantly puts us on our toes so that we’re always exploring what we’re given and not just taking it wholesale.”

He believes there is no real end to postmodernism – only “post, post, post, post, post, postmodernism”.

Though Desmond’s writing is fresh, interesting and thought-provoking, it is also experimental and complex. Not all his readers are able to readily understand it. So, Desmond was surprised that his I Didn’t Know Mani Was a Conceptualist (2014) won in the Poetry Category at the 2016 Singapore Literature Prize.

“It’s not very accessible,” he admits, referring to his writing, “so for the judges to give a nod to it was a very nice signal to the literary community in Singapore that they were opening the doors to allow very different kinds of work.”

Desmond is also incredibly appreciative of his readers who have been supporting him.

“They’ve been forthcoming and kind and generous even when they didn’t understand the book completely… They felt that there was something in there that was new. That the voice was innovative, that it was trying to break new boundaries, and that was one of the big reasons that I wrote the book.”